You are here

Most HVAC systems heat or cool forced air.

The components and layout of mechanical air distribution are important because they can improve both the comfort of occupied spaces and reduce energy use. Although the fans that distribute the air do not consume nearly as much energy as the equipment that generates the heating and cooling, it doesn’t matter how efficient the equipment is if the air is not distributed well. Furthermore, leaky ductwork can cause 20 - 40% of heating and cooling energy loss.1

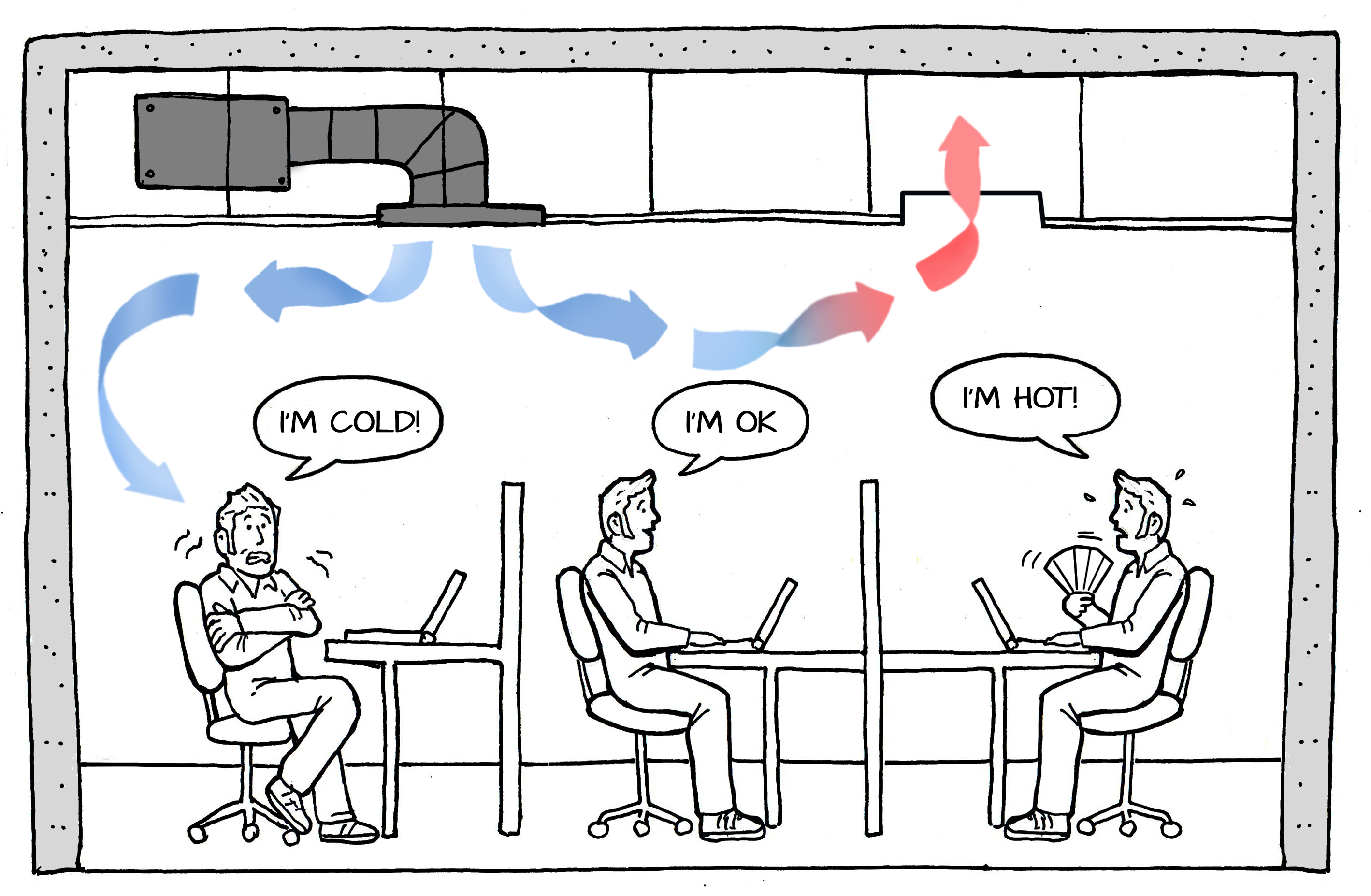

Heating and cooling must be well-distributed for everyone to be comfortable.

Successful air distribution is measured both by its thermal comfort performance and its energy efficiency. The efficiency of air handling systems can be holistically measured by measuring the electricity use of the fans.

Delivering Heating And Cooling

Small-scale HVAC units can simply pull room air in, heat or cool it, and return it to the room. However, systems for large buildings are much more complex.

Large buildings typically have HVAC central plants that use chilled water ("CHW") and hot water ("HW") to move heating and cooling to central air handlers. From there, the heated or cooled air is delivered to different rooms and/or cooling zones by mechanical air distribution systems, which are comprised of ducts or plenums, fans, and dampers to adjust the volume of air entering occupied spaces.

Dehumidification is also delivered along with cooling (see humidity control).

Also, the most efficient systems by supplement or replace forced air systems with radiant temperature systems, passive heating, and/or natural ventilation.

Where to Heat and Cool

The first step in keeping occupants comfortable with an HVAC system is to understand where and when you’ll need to heat and cool, and setting up an appropriate “zoning” strategy.

Efficient HVAC design starts with the architect, whether they know it or not. Architects can enable less complicated and energy-intensive mechanical systems by creating spaces that avoid hot spots and cold spots, or separating areas that receive more or less passive heat so they can use separate HVAC zones.

Zones

Zones are locations in the building that have different heating or cooling needs. This can be the result of a different activity within different spaces (exercise room vs. meeting room), different room occupancy, or different loads on different spaces.

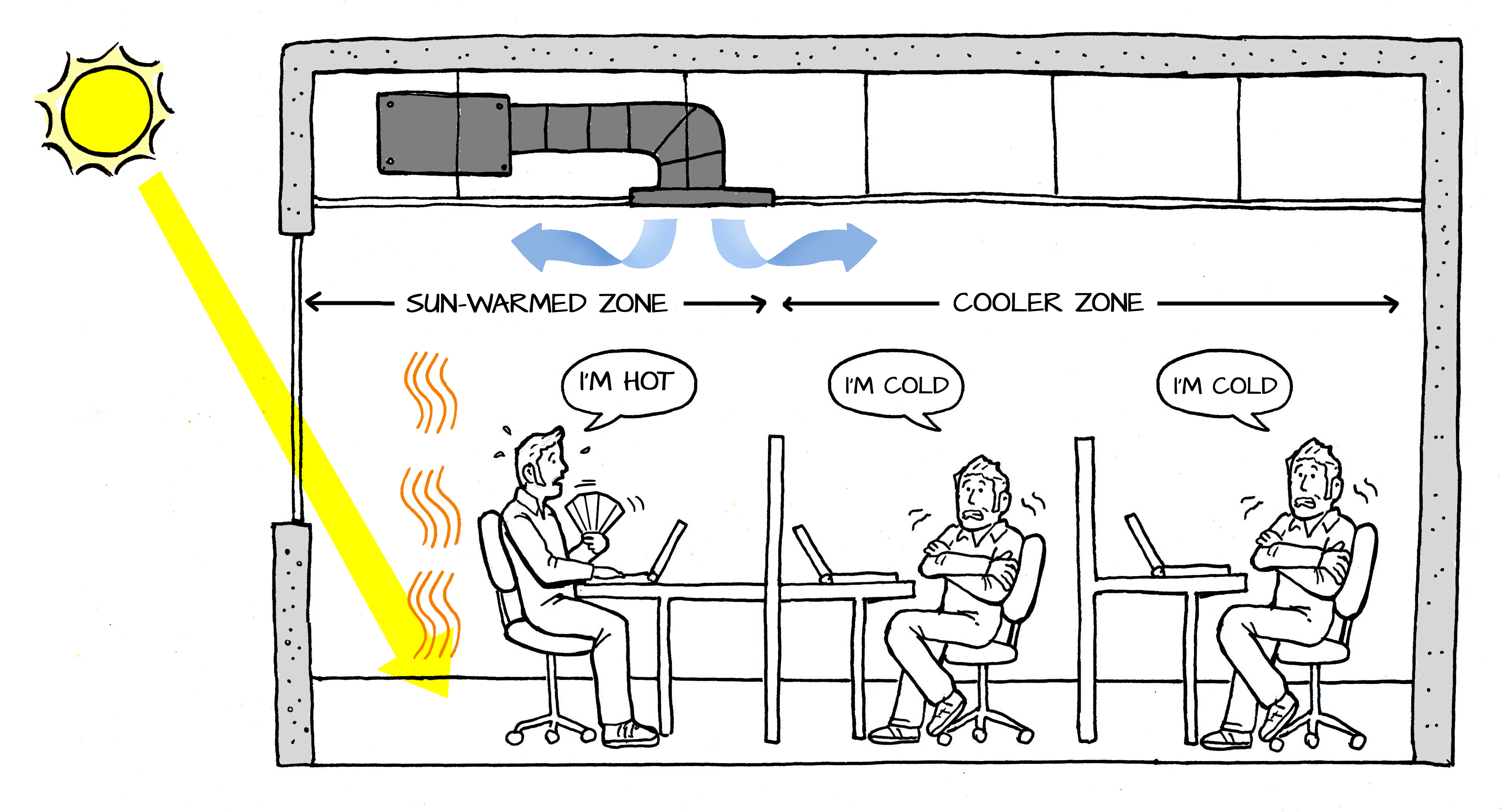

Each room may be a different zone, one zone might contain several rooms, or one room might contain more than one zone (particularly if it is a deep room with one side of large sun-facing windows). In deep buildings, areas away from direct influence of outside sun or other effects are called “core” zones. Comfort here usually has to be provided entirely by active HVAC systems.

Hot Spots and Cold Spots

Unfortunately, HVAC distribution is never as simple as just pumping in hot air when it is too cold and cold air when it is too hot. The person sitting in the summer sun next to the window may be quite comfortable while those at their desks near the elevator core are freezing. Such a situation requires complex zoning strategies.

One room may require multiple temperature zones

In centralized HVAC systems, sometimes cold spots are dealt with by putting separate small heaters on the air outlets. Then, when the chiller on the roof produces air at 12°C to meet the requirements of the person by the window, the heaters near the elevators can heat the air back up to 16°C so that the people there do not freeze. Such a system is obviously inefficient – and should be avoided.

Serving Different Zones

Different zones can be given warmer or cooler air by having separate HVAC units and separate ductwork paths, though this is generally costly.

Increasing or decreasing the airflow (with the same temperature air) in different zones is cheaper and more common. This can be provided most easily and cheaply with dampers, or with different fans and duct systems for more extreme situations.

Designing systems that individual occupants can adjust is also helpful. This way everyone can be comfortable, whether they are in a warmer spot or cooler spot, are wearing lighter or heavier clothing, or simply like to be warmer or cooler than others. Human comfort is subjective, and if people aren’t comfortable in your building it will compromise all of your efforts at energy efficiency.

Equipment for Delivering Air

Centralized system will generally have its heating and cooling equipment tucked away in a maintenance room and/or the roof, and will move heated or cooled air to different zones by ducts or plenums, fans, and dampers.

Ducts and Plenums

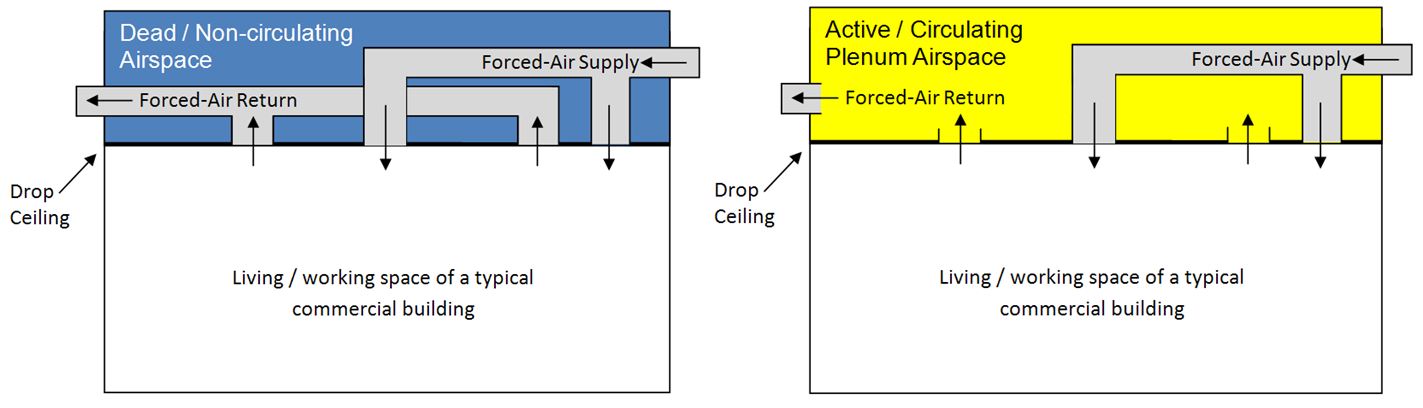

Ducts or plenums provide the pathways for air. Plenums are more open spaces for air circulation, while ductwork provides defined pathways.

Ducts vs. plenums (image source: Wikipedia)

There must always be a supply path and a return or exhaust path. The return path generally brings used air back to be recycled into the building but mixed with some percentage of outside air to maintain freshness. This saves energy, as it avoids conditioning more outside air. However, some laboratories and other programs require 100% outside air for health and safety.

![]()

Ductwork exposed in a building without a drop ceiling.

Plenums can provide less resistance to airflow and have slower-moving air. While this can be advantageous, they can also be more expensive and are not appropriate for space-constrained buildings.

Fans

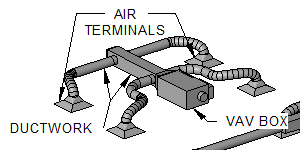

Fans push or pull air around the system. The simplest air distribution systems use constant fan speed and constant-size damper openings. However, Variable Air Volume ("VAV") systems change fan speed on the fly, saving up to 10 - 20% of HVAC energy use.

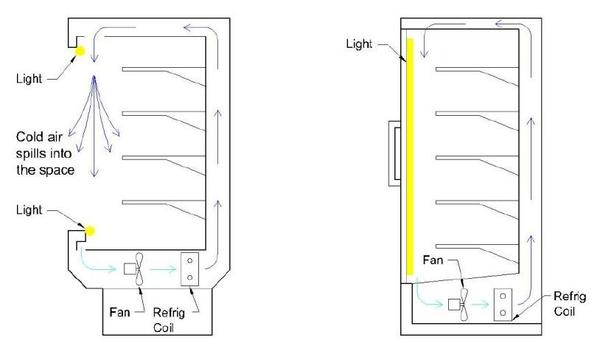

Variable Air Volume fan system (image source: Wikipedia)

Dampers

Vents or dampers are valves that allow some or all of the airflow through a duct to be cut off. They can be manually operated by building occupants, or automatically operated by centralized control systems.

Dampers are the simplest and least expensive way to regulate the amount of heating, cooling, and ventilation to different parts of a room or building. However, they cause resistance to air flow, which makes fans operate less efficiently, so they should not be overused.

1 From Lawrence Berkeley Labs