You are here

Steven Vogel's book Cats' Paws and Catapults contains an excellent list of nature's design principles for mechanical engineers1. It is reproduced here, with some editing for brevity and links. For more explanation of the principles, see the book.

"Nature uses fewer flat and more curved surfaces than we do", for better lightweighting.

Corners in our technology are abrupt; nature's are generally rounded, to avoid stress concentrations.

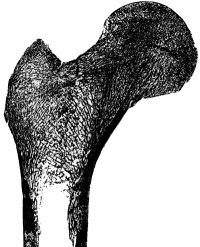

|

Bone is a single material that varies a great deal in its construction. (Modified from Wikimedia Commons) |

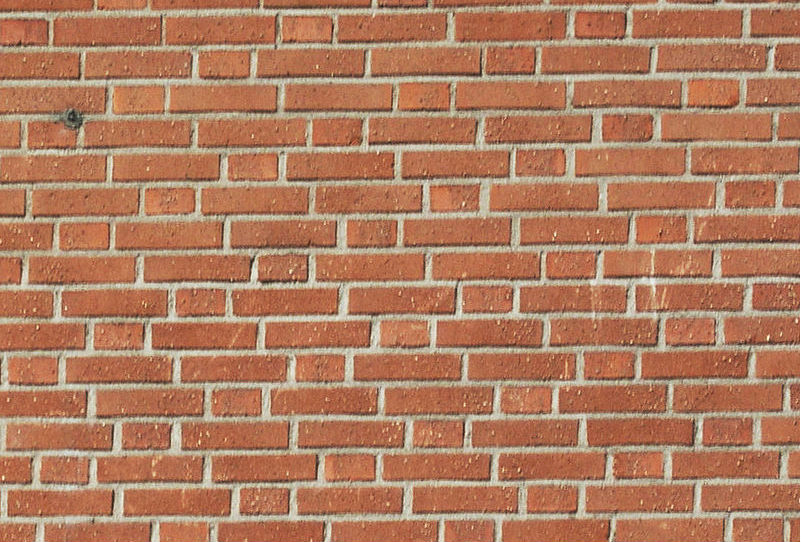

Brick walls (left) are generally built for stiffness;

abalone shells (right) are like a brick wall in their microstructure,

but with flexible "mortar" that makes them twice as strong

and a thousand times tougher than their "bricks" alone. (Image Sources 1, 2)

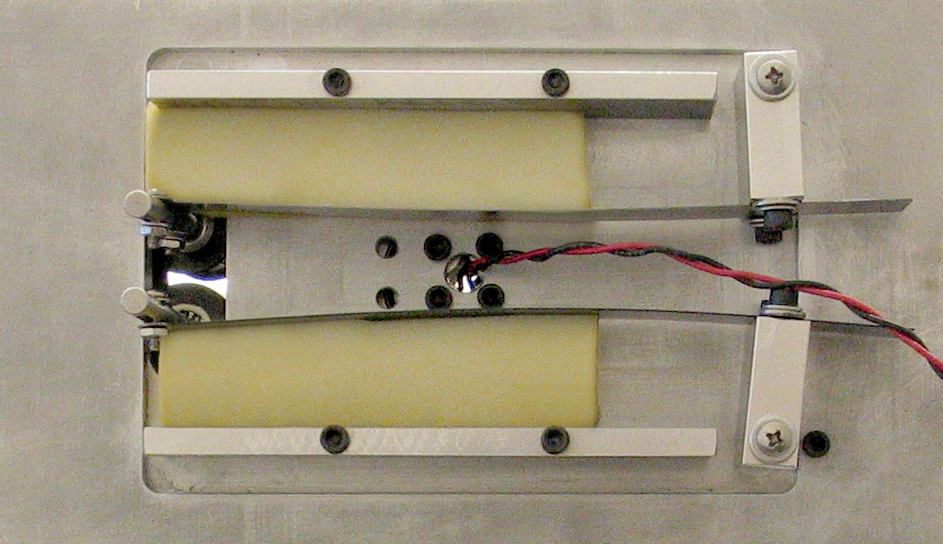

This vibration damping system for film soundtrack readers

replaced roughly $50 of rigid machined arms, high-precision ball bearings,

springs, and an air shock absorber with roughly $1.50 of spring steel

and viscoelastic foam, for the same noise reduction.

(Photo and device design: Jeremy Faludi)

|

Jellyfish are not streamlined rigid bodies; rather, they change their shape to move through water. (Photo: Jeremy Faludi) |

The Eiffel Tower uses steel to bend rather than break under stress;

trees use wood, a foamed composite, to do the same. (Photos: Jeremy Faludi)

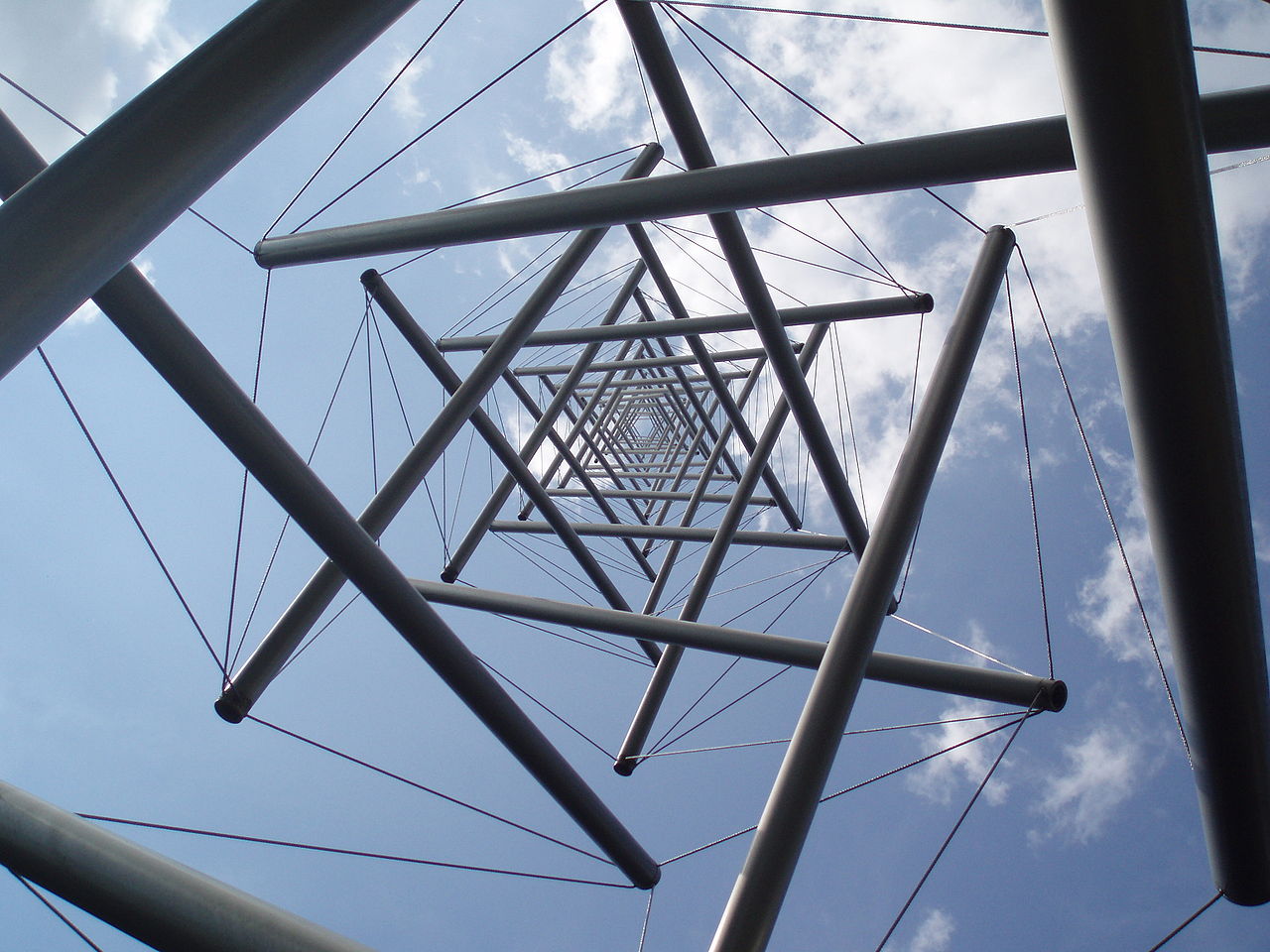

Kenneth Snelson's sculpture "Needle Tower" uses tensegrity for its extremely lightweight form.

(Wikimedia Commons)

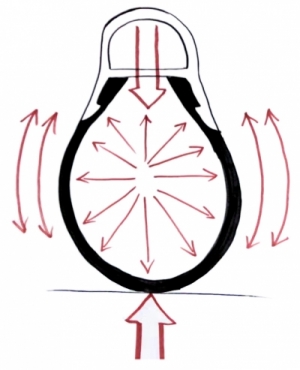

Tires are one of the few places we use fluid pressure to create structure.

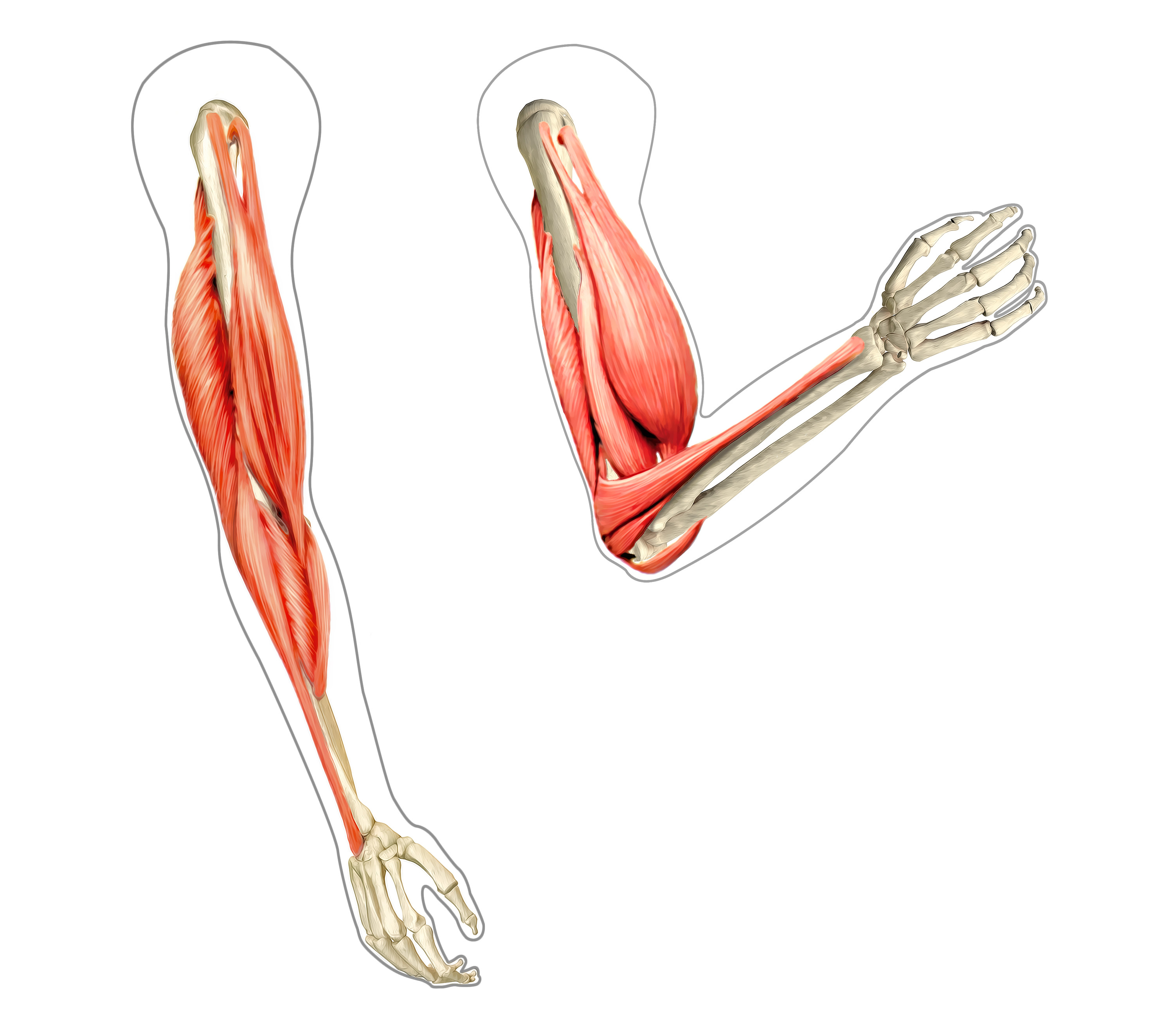

Muscles work by contracting linearly.

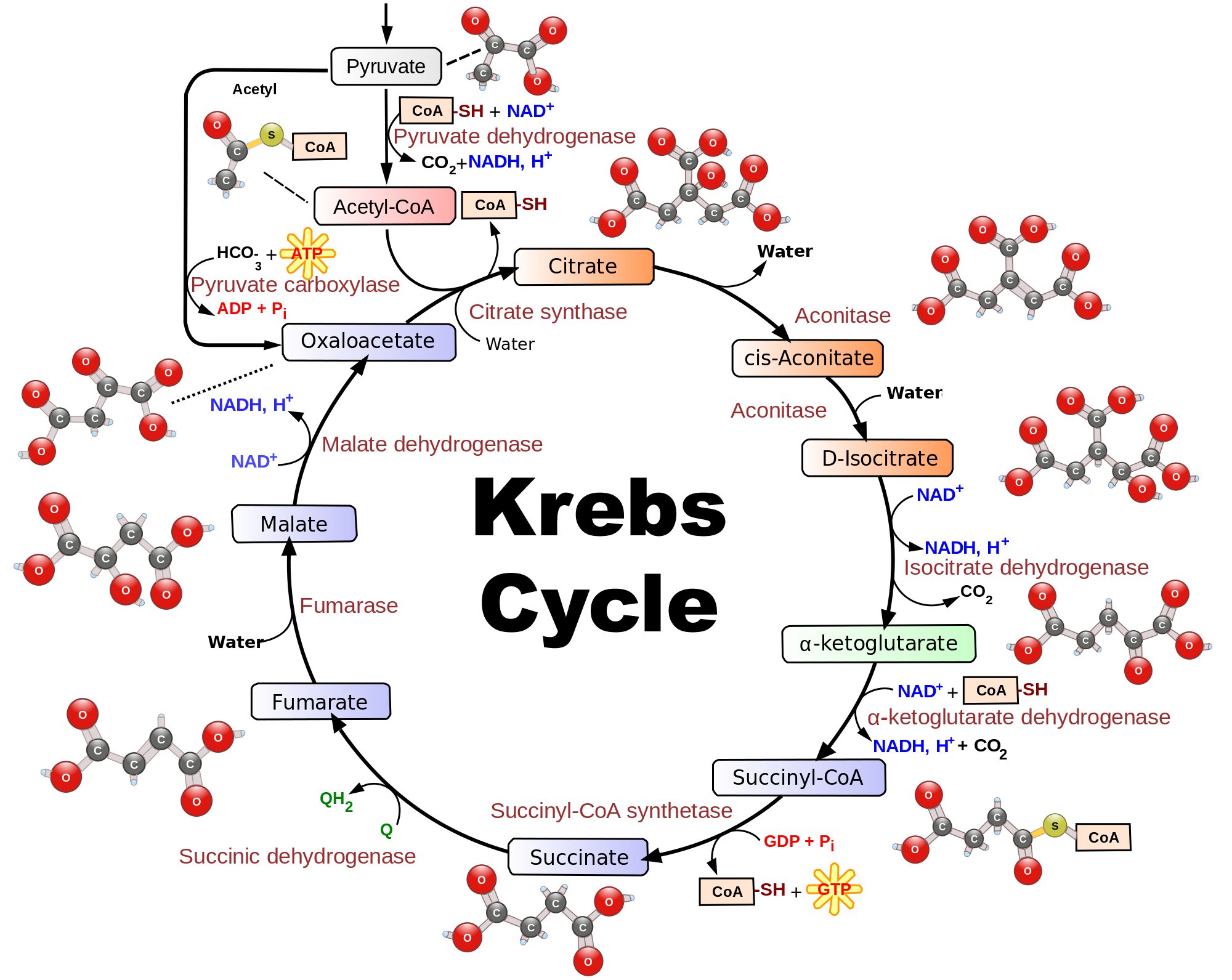

The Krebs cycle is how humans and many other organisms turn

food into energy in our bodies. It is an isothermal reaction.

(Modified from Wikimedia Commons)

Kangaroos' Achilles tendons capture the energy from hitting the ground

as elastic energy, and re-release it for the next jump.

While many birds pass time on the water's surface, they either fly or dive for serious locomotion.

Moving on the surface causes too much drag at high speed. (Wikimedia Commons)

A type of concrete invented at the University of Michigan's Materials Research Lab

heals itself after cracking, through special chemical reactions with air.

(From AskNature.org)

1Vogel, S. "Cats’ paws and catapults: mechanical worlds of nature and people" WW Norton & Company, New York, 1998. pp.289-291.